Names of God in Judaism

| Part of a series on | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Judaism | |||

| Portal | Category | |||

| Jewish religious movements | |||

| Orthodox (Haredi · Hasidic · Modern) | |||

| Conservative · Reform | |||

| Karaite · Reconstructionist · Renewal · Humanistic | |||

| Jewish philosophy | |||

| Principles of faith · Kabbalah · Messiah · Ethics | |||

| Chosenness · Names of God · Musar | |||

| Religious texts | |||

| Tanakh (Torah · Nevi'im · Ketuvim) | |||

| Ḥumash · Siddur · Piyutim · Zohar | |||

| Rabbinic literature (Talmud · Midrash · Tosefta) | |||

| Religious Law | |||

| Mishneh Torah · Tur | |||

| Shulchan Aruch · Mishnah Berurah | |||

| Kashrut · Tzniut · Tzedakah · Niddah · Noahide laws | |||

| Holy cities | |||

| Jerusalem · Safed · Hebron · Tiberias | |||

| Important figures | |||

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob | |||

| Moses · Aaron · David · Solomon | |||

| Sarah · Rebecca · Rachel · Leah | |||

| Rabbinic sages | |||

| Jewish life cycle | |||

| Brit · Pidyon haben · Bar/Bat Mitzvah | |||

| Marriage · Bereavement | |||

| Religious roles | |||

| Rabbi · Rebbe · Posek · Hazzan/Cantor | |||

| Dayan · Rosh yeshiva · Mohel · Kohen/Priest | |||

| Religious buildings & institutions | |||

| Synagogue · Beth midrash · Mikveh | |||

| Sukkah · Chevra kadisha | |||

| Holy Temple / Tabernacle | |||

| Jewish education | |||

| Yeshiva · Kollel · Cheder | |||

| Religious articles | |||

| Sefer Torah · Tallit · Tefillin · Tzitzit · Kippah | |||

| Mezuzah · Hanukiah/Menorah · Shofar | |||

| 4 Species · Kittel · Gartel | |||

| Jewish prayers and services | |||

| Shema · Amidah · Aleinu · Kaddish · Minyan | |||

| Birkat Hamazon · Shehecheyanu · Hallel | |||

| Havdalah · Tachanun · Kol Nidre · Selichot | |||

| Judaism & other religions | |||

| Christianity · Islam · Judeo-Christian | |||

| Abrahamic faiths · Pluralism · Others | |||

| Related topics | |||

| Antisemitism · Criticism · Holocaust · Israel · Zionism | |||

In Judaism, the name of God is more than a distinguishing title; it represents the Jewish conception of the divine nature, and of the relationship of God to the Jewish people and to the world. To demonstrate the sacredness of the names of God, and as a means of showing respect and reverence for them, the scribes of sacred texts treat them with absolute sanctity when writing and speaking them. The various titles for God in Judaism represent God as He is known, as well as the divine aspects which are attributed to Him.

The numerous titles for God have been a source of debate amongst biblical scholars. Some have advanced the variety as proof that the Torah, the main scripture of Judaism, has many authors (see documentary hypothesis). YHWH is the only proper "name of God" in the Tanakh, in the sense that Abraham or Sarah are proper names by which you call a person. Whereas words such as Elohim (god, or authority), El (mighty one), Shaddai (almighty), Adonai (master), Elyon (most high), Avinu (our father), etc. are not names but titles, highlighting different aspects of YHWH, and the various roles which God has. This is similar to how someone may be called 'father', 'husband', 'brother', 'son', etc, but their personal name is the only one that can be correctly identified as their actual designation. In the Tanakh, YHWH is the personal name of the God of Israel, whereas other 'names' are titles which are ascribed to God.

Contents |

Names of God

The Tetragrammaton

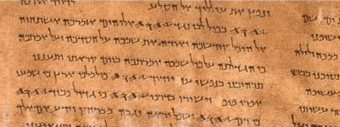

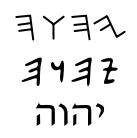

The most important and most often written name of God in Judaism is the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God, also known as יהוה, or YHWH. "Tetragrammaton" derives from the prefix tetra- ("four") and gramma ("letter", "grapheme"). The Tetragrammaton appears 6,828 times in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia edition of the Hebrew Masoretic text. This name is first mentioned in the Book of Genesis (2.4) and in English language bibles is traditionally translated as "The Lord".

(The epithet "The Eternal One" may increasingly be found instead, particularly in Progressive Jewish communities seeking to use gender-neutral language[1]). Because Judaism forbids pronouncing the name outside the Temple in Jerusalem, the correct pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton may have been lost, as the original Hebrew texts only included consonants. The Hebrew letters are named Yod-Heh-Vav-Heh: יהוה. In English it is written as YHWH, YHVH, or JHVH depending on the transliteration convention that is used. The Tetragrammaton was written in contrasting Paleo-Hebrew characters in some of the oldest surviving square Aramaic Hebrew texts, and were not read as Adonai ("My Lord") until after the Rabbinic teachings after Israel went into Babylonian captivity.[2]

In appearance, YHWH is an archaic third person singular imperfect of the verb "to be", meaning, therefore, "He is". This explanation agrees with the meaning of the name given in Exodus 3:14, where God is represented as speaking, and hence as using the first person — "I am". It stems from the Hebrew conception of monotheism that God exists by himself for himself, and is the uncreated Creator who is independent of any concept, force, or entity; therefore "I am that I am".

The idea of 'life' has been traditionally connected with the name YHWH from medieval times. Its owner is presented as a living God, as contrasted with the lifeless gods of the 'heathen' polytheists: God is presented as the source and author of life (compare 1 Kings 18; Isaiah 41:26–29, 44:6–20; Jeremiah 10:10, 14; Genesis 2:7; and so forth).

The prohibition of blasphemy, for which capital punishment is prescribed in Jewish law, refers only to the Tetragrammaton (Soferim iv., end; comp. Sanh. 66a).

The name YHWH is likely to be the origin of the Yao of Gnosticism. A minority view considers it to be cognate to an uncertain reading "Yaw" for the god Yam in damaged text of the Baal Epic. Though the final Heh in YHWH might not have been pronounced in classical Hebrew, the medial Heh would have almost certainly been pronounced thus the roots of the alleged Yaw and "YHWH" are different. Other possible vocalizations include a mappiq in the final Heh, rendering it pronounced — most likely with a gliding Patah (a-sound) before it.

Pronouncing the tetragrammaton

In the Masoretic Text the name YHWH is vowel pointed as יְהֹוָה, pronounced Yehovah in modern Hebrew, and Yəhōwāh in Tiberian Vocalization. Traditionally in Judaism, the name is not pronounced but read as Adonai, "my Lord" during prayer, and referred to as HaShem, "the Name" at all other times. This is done out of hesitation to pronounce the name in the absence of the Temple in Jerusalem, due to its holiness. This tradition has been citied by most scholars as evidence that the Masoretes vowel pointed YHWH as they did, to indicate to the reader they are to pronounce "Adonai" in its place. While the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי (Aḏōnáy) and יְהֹוָה (Yəhōwāh) are very similar, they are not identical. This may indicate the Masoretic vowel pointing was done in truth and not only as a Qere-Ketiv.[3] The name YHWH was theorized as Yahweh by 19th century scholars based on circumstantial historical and linguistic evidence. Most scholars do not view it as an "accurate" reconstruction in an absolute sense, but as one possible guess. See Yahweh for a more detailed explanation of this reconstruction.

Traditional Judaism teaches that the four-letter name of God, YHWH, is forbidden to be uttered except by the High Priest in the Holy Temple on Yom Kippur. Throughout the entire Yom Kippur service, the High Priest pronounces the name YHWH "just as it is written" in each blessing he makes. When the people standing in the Temple courtyard hear the name they prostrate flat on the Temple floor. Since the Temple in Jerusalem does not exist today, this name is never said in religious rituals by Jews, and the correct pronunciation is currently disputed. Orthodox and some Conservative Jews never pronounce it for any reason. Some religious non-Orthodox Jews are willing to pronounce it, but for educational purposes only, and never in casual conversation or in prayer. Instead of pronouncing YHWH during prayer, Jews say Adonai.

Substituting Adonai for YHWH dates back at least to the 3rd century BCE.[4] Passages such as:

- "And, behold, Boaz came from Bethlehem, and said unto the reapers, YHWH [be] with you. And they answered him, YHWH bless thee" (Ruth 2:4)

strongly indicate that there was a time when the name was in common usage. Also the fact that many Hebrew names consist of verb forms contracted with the tetragrammaton indicates that the people knew the verbalization of the name in order to understand the connection. The prohibition against verbalizing the name never applied to the forms of the name within these contractions (the prefixes yeho-, yo-, and the suffixes -yahu, -yah) and their pronunciation remains known. (These known pronunciations do not in fact match the conjectured pronunciation yahweh for the stand alone form. However they do match the form Yəhōwāh as vowel pointed in the Masoretic Text.)

Many English translations of the Bible, following the tradition started by William Tyndale, render YHWH as "LORD" (all caps) or "Lord" (small caps), and Adonai as "Lord" (upper & lower case). In a few cases, where "Lord YHWH" (Adonai YHWH) appears, the combination is written as "Lord God" (Adonai elohim). While neither "Jehovah" or "Yahweh" is recognized in Judaism, a number of Bibles, mostly Christian, use the name. The Jewish Publication Society translation of 1917, in online versions does use Jehovah once at Exodus 6:3, where this footnote appears in the electronic version: The Hebrew word (four Hebrew letters: HE, VAV, HE, YOD,) remained in the English text untranslated; the English word 'Jehovah' was substituted for this Hebrew word. The footnote for this Hebrew word is: "The ineffable name, read Adonai, which means the Lord." ] Electronic versions available today can be found at E-Sword or The Sword Project (BUT also see below footnote re: Breslov.com version.)

The translation "Jehovah" may have been formed by adding the vowel points of "Adonai." Early Christian translators of the Torah took the letters "IHVH," from the Latin Vulgate, and the vowels "a-o-a" were inserted into the text rendering IAHOVAH or "Iehovah" in 16th century English, which later became "Jehovah." The form "Jehovah" has been used in English bibles from the time of William Tyndale (See Yahweh, for why Jehovah is considered an error by some.) in 1530, including:

- Coverdale's Bible [1535];

- the Matthew Bible [1537];

- the Bishops' Bible [1568];

- the Geneva Bible [1560].

(for each of the preceding, in print these have 'Iehouah,' which in modern pronunciation equals Jehovah).

"Jehovah" is also found in the King James Bible, the American Standard Version, the Darby Bible, Green's Literal Translation also known as the LITV, Young's Literal Translation, the 1925 Italian Riveduta Luzzi version, the MKJV [1998], the New English Bible and the New World Translation.

"Yahweh" (or a similar construction) is found in the Rotherham's Emphasized Bible [1902], the New Jerusalem Bible, the World English Bible [in the Public Domain without copyright], the Amplified Bible [1987], the Holman Christian Standard Bible [2003], The Message (Bible) [2002], and the Bible in Basic English [1949/1964].

(As of 2007[update], the Breslov.com revised copy of the electronic Jewish Publication Society of America Version [1917] contains a single occurrence of "Jehovah" at Exodus 6.3 since at least 2001, but it seems to be a conversion error.[5])

HaShem

Halakha requires that secondary rules be placed around the primary law, to reduce the chance that the main law will be broken. As such, it is common Jewish practice to restrict the use of the word Adonai to prayer only. In conversation, many Jewish people, even when not speaking Hebrew, will call God "HaShem", השם, which is Hebrew for "the Name" (this appears in Leviticus 24:11). Many Jews extend this prohibition to some of the other names listed below, and will add additional sounds to alter the pronunciation of a name when using it outside of a liturgical context, such as replacing the 'h' with a 'k' in names of God such as 'kel' and 'elokim'.

While other names of God in Judaism are generally restricted to use in a liturgical context, HaShem is used in more casual circumstances. HaShem is used by Orthodox Jews so as to avoid saying Adonai outside of a ritual context. For example, when some Orthodox Jews make audio recordings of prayer services, they generally substitute HaShem for Adonai; others will say Amonai. [6] On some occasions, similar sounds are used for authenticity, as in the movie Ushpizin, where Abonai Elokenu [sic] is used throughout.

Adoshem

Up until the mid twentieth century, however, another convention was quite common, the use of the word, Adoshem - combining the first two syllables of the word Adonai with the last syllable of the word Hashem. This convention was discouraged by Rabbi David HaLevi Segal (known as the Taz) in his commentary to the Shulchan Aruch. However, it took a few centuries for the word to fall into almost complete disuse. The rationale behind the Taz's reasoning was that it is disrespectful to combine a Name of God with another word. Despite being obsolete in most circles, it is used occasionally in conversation in place of Adonai by Orthodox Jews who do not wish to say Adonai but need to specify the use of the particular word as opposed to God.

Other names or titles of God

Adonai

Jews also call God Adonai, Hebrew for "Lord" (Hebrew: אֲדֹנָי) or A-D-N. Formally, this is plural ("my Lords"), but the plural is usually construed as a respectful, and not a syntactic plural. (The singular form is Adoni, "my lord". This was used by the Phoenicians for the god Tammuz and is the origin of the Greek name Adonis. Jews only use the singular to refer to a distinguished person: in the plural, "rabotai", literally, "my masters", is used in both Mishnaic and modern Hebrew.)

Since pronouncing YHWH is avoided out of reverence for the holiness of the name, Jews use Adonai instead in prayers, and colloquially would use Hashem ("the Name"). When the Masoretes added vowel pointings to the text of the Hebrew Bible around the eighth century CE, they gave the word YHWH vowels very similar to that of Adonai. Tradition has dictated this is to remind the reader to say Adonai instead. Later Biblical scholars took this vowel substitution for the actual spelling of YHWH and interpreted the name of God as Jehovah.

The Sephardi translators of the Ferrara Bible go further and substitute Adonai with A.

Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh

Ehyeh asher ehyeh (Hebrew: אהיה אשר אהיה) is the sole response given to Moses when he asks for God's name (Exodus 3:14). It is one of the most famous verses in the Hebrew Bible. The Tetragrammaton itself derives from the same verbal root. The King James version of the Bible translates the Hebrew as "I am that I am" and uses it as a proper name for God. The Aramaic Targum Onkelos leaves the phrase untranslated and is so quoted in the Talmud (B. B. 73a).

Ehyeh is the first-person singular imperfect form of hayah, "to be". Ehyeh is usually translated "I will be," since the imperfect tense in Hebrew denotes actions that are not yet completed (e.g. Exodus 3:12, "Certainly I will be [ehyeh] with thee.")[7].

Asher is an ambiguous pronoun which can mean, depending on context, "that", "who", "which", or "where".[8].

Therefore, although Ehyeh asher ehyeh is generally rendered in English "I am that I am," better renderings might be "I will be what I will be" or "I will be who I will be", or even "I will be because I will be."[9]. In these renderings, the phrase becomes an open-ended gloss on God's promise in Exodus 3:12. Other renderings include: Leeser, “I WILL BE THAT I WILL BE”; Rotherham, “I Will Become whatsoever I please.” Greek, Ego eimi ho on (ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν), "I am The Being" in the Septuagint[10], and Philo[11][12], and Revelation[13]” or, “I am The Existing One”; Lat., ego sum qui sum, “I am Who I am.” [14].

El

El appears Ugaritic, Phoenician and other 2nd and 1st millennium BCE texts both as generic "god" and as the head of the divine pantheon.[15] In the Hebrew bible El (Hebrew: אל) appears very occasionally alone (e.g. Genesis 33:20, el elohe yisrael, "El the god of Israel", and Genesis 46:3, ha'el elohe akiba, "El the god of your father"), but usually with some epithet or attribute attached, (e.g. El Elyon, "Most High El", El Shaddai, "El of Shaddai", El `Olam "Everlasting El", El Hai, "Living El", El Ro'i "El of Seeing", and El Gibbor "El of Strength"), in which cases it can be understood as the generic "god". In theophoric names such as Gabriel ("Strength of God"), Michael ("Who is like God?"), Raphael ("God's medicine"), Ariel ("God's lion"), Daniel ("God's Judgement"), Israel ("one who has struggled with God"), Immanuel ("God is with us"), and Ishmael ("God Hears"/"God Listens") it usually interpreted and translated as "God", but it is not clear whether these "el"s refer to deity in general or to the god El in particular.[16]

Elah

For other uses see Elah

Elah (Hebrew: אֵלָה), (plural "elim") is the Aramaic word for “awesome“. The origin of the word is uncertain and it may be related to a root word, meaning “fear” or “reverence.” Elah is found in the Tanakh in the books of Ezra, Daniel and Jeremiah (Jer 10:11, the only verse in the entire book written in Aramaic.)[17] Elah is used to describe both pagan gods and the one true God.

- Elah-avahati - God of my fathers, (Daniel 2:23)

- Elah Elahin - God of gods (Daniel 2:47)

- Elah Yerushelem - God of Jerusalem (Ezra 7:19)

- Elah Yisrael - God of Israel (Ezra 5:1)

- Elah Shemaya - God of Heaven (Ezra 7:23)

Elohim

A common name of God in the Hebrew Bible is Elohim (Hebrew: אלהים).

Despite the -im ending common to many plural nouns in Hebrew, the word Elohim, when referring to God is grammatically singular, and takes a singular verb in the Hebrew Bible. The word is identical to the usual plural of el meaning gods or magistrates, and is cognate to the 'lhm found in Ugaritic, where it is used for the pantheon of Canaanite Gods, the children of El and conventionally vocalized as "Elohim" although the original Ugaritic vowels are unknown. When the Hebrew Bible uses elohim not in reference to God, it is plural (for example, Exodus 20:3). There are a few other such uses in Hebrew, for example Behemoth. In Modern Hebrew, the singular word ba'alim ("owner") looks plural, but likewise takes a singular verb.

A number of scholars have traced the etymology to the Semitic root *yl, "to be first, powerful", despite some difficulties with this view.[18] Elohim is thus the plural construct "powers". Hebrew grammar allows for this form to mean "He is the Power (singular) over powers (plural)", just as the word Ba'alim means "owner" (see above). "He is lord (singular) even over any of those things that he owns that are lordly (plural)."

Other scholars interpret the -im ending as an expression of majesty (pluralis majestatis) or excellence (pluralis excellentiae), expressing high dignity or greatness: compare with the similar use of plurals of ba`al (master) and adon (lord). For these reasons many Trinitarians cite the apparent plurality of elohim as evidence for the basic Trinitarian doctrine of the Trinity. This was a traditional position but there are some modern Christian theologians who consider this to be an exegetical fallacy.

Theologians who dispute this claim cite the hypothesis that plurals of majesty came about in more modern times. Richard Toporoski, a classics scholar, asserts that plurals of majesty first appeared in the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE).[19] Indeed, Gesenius states in his book Hebrew Grammar the following:[20]

The Jewish grammarians call such plurals … plur. virium or virtutum; later grammarians call them plur. excellentiae, magnitudinis, or plur. maiestaticus. This last name may have been suggested by the we used by kings when speaking of themselves (compare 1 Maccabees 10:19 and 11:31); and the plural used by God in Genesis 1:26 and 11:7; Isaiah 6:8 has been incorrectly explained in this way). It is, however, either communicative (including the attendant angels: so at all events in Isaiah 6:8 and Genesis 3:22), or according to others, an indication of the fullness of power and might implied. It is best explained as a plural of self-deliberation. The use of the plural as a form of respectful address is quite foreign to Hebrew.

The plural form ending in -im can also be understood as denoting abstraction, as in the Hebrew words chayyim ("life") or betulim ("virginity"). If understood this way, Elohim means "divinity" or "deity". The word chayyim is similarly syntactically singular when used as a name but syntactically plural otherwise.

The Hebrew form Eloah (אלוהּ, which looks as though it might be a singular feminine form of Elohim) is comparatively rare, occurring only in poetry and late prose (in the Book of Job, 41 times). What is probably the same divine name is found in Arabic (Ilah as singular "a god", as opposed to Allah meaning "The God" or "God") and in Aramaic (Elaha). This unusual singular form is used in six places for heathen deities (examples: 2 Chronicles 32:15; Daniel 11:37, 38;). The normal Elohim form is also used in the plural a few times, either for gods or images (Exodus 9:1, 12:12, 20:3; and so forth) or for one god (Exodus 32:1; Genesis 31:30, 32; and elsewhere). In the great majority of cases both are used as names of the One God of Israel.

Eloah, Elohim, means "He who is the object of fear or reverence", or "He with whom one who is afraid takes refuge". Another theory is that it is derived from the Semitic root "uhl" meaning "to be strong". Elohim then would mean "the all-powerful One", based on the usage of the word "el" in certain verses to denote power or might (Genesis 31:29, Nehemiah 5:5).

In many of the passages in which elohim [lower case] occurs in the Bible it refers to non-Israelite deities, or in some instances to powerful men or judges, and even angels (Exodus 21:6, Psalms 8:5).

`Elyon

The name `Elyon (Hebrew: עליון) occurs in combination with El, YHWH or Elohim, and also alone. It appears chiefly in poetic and later Biblical passages. The modern Hebrew adjective "`Elyon" means "supreme" (as in "Supreme Court") or "Most High". El Elyon has been traditionally translated into English as 'God Most High'. The Phoenicians used what appears to be a similar name for God, Έλιον. It is cognate to the Arabic `Aliyy.

Roi

In the Hebrew bible Book of Genesis, specifically Gen 16:13, Hagar calls the divine protagonist, El Roi. Roi means “seeing". To Hagar, God revealed Himself as “The God Who sees".

Shaddai

Shaddai was a late Bronze Age Amorite city on the banks of the Euphrates river, in northern Syria. The site of its ruin-mound is called Tell eth-Thadyen: "Thadyen" being the modern Arabic rendering of the original West Semitic "Shaddai". It has been conjectured that El Shaddai was therefore the "god of Shaddai" and associated in tradition with Abraham, and the inclusion of the Abraham stories into the Hebrew Bible may have brought the northern name with them (see Documentary hypothesis).

In the vision of Balaam recorded in the Book of Numbers 24:4 and 16, the vision comes from Shaddai along with El. In the fragmentary inscriptions at Deir Alla, though Shaddai is not, or not fully present,[21] shaddayin appear, less figurations of Shaddai.[22] These have been tentatively identified with the ŝedim of Deuteronomy 34:17 and Psalm 106:37-38,[23] who are Canaanite deities.

According to Exodus 6:2, 3, Shaddai is the name by which God was known to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The name Shaddai (Hebrew: שַׁדַּי) is used as a name of God later in the Book of Job.

In the Septuagint and other early translations Shaddai was translated with words meaning "Almighty". The root word "shadad" (שדד) means "to overpower" or "to destroy". This would give Shaddai the meaning of "destroyer" as one of the aspects of God. Thus it is essentially an epithet.

Another theory is that Shaddai is a derivation of a Semitic stem that appears in the Akkadian shadû ("mountain") and shaddā`û or shaddû`a ("mountain-dweller"), one of the names of Amurru. This theory was popularized by W. F. Albright but was somewhat weakened when it was noticed that the doubling of the medial d is first documented only in the Neo-Assyrian period. However, the doubling in Hebrew might possibly be secondary. In this theory God is seen as inhabiting a mythical holy mountain, a concept not unknown in ancient West Asian mythology (see El), and also evident in the Syriac Christian writings of Ephrem the Syrian, who places Eden on an inaccessible mountaintop.

An alternative view proposed by Albright is that the name is connected to shadayim which means "breasts" in Hebrew. It may thus be connected to the notion of God’s fertility and blessings of the human race. In several instances it is connected with fruitfulness: "May God Almighty [El Shaddai] bless you and make you fruitful and increase your numbers…" (Gen. 28:3). "I am God Almighty [El Shaddai]: be fruitful and increase in number" (Gen. 35:11). "By the Almighty [El Shaddai] who will bless you with blessings of heaven above, blessings of the deep that lies beneath, blessings of the breasts [shadayim] and of the womb [racham]" (Gen. 49:25). Harriet Lutzky has presented evidence that Shaddai was an attribute of a Semitic goddess, linking the epithet with Hebrew šad "breast" as "the one of the Breast", as Asherah at Ugarit is "the one of the Womb".[24]

It is also given a Midrashic interpretation as an acronym standing for "Guardian of the Doors of Israel" (Hebrew: שׁוֹמֶר דְלָתוֹת יִשְׂרָאֶל). This acronym, which is commonly found as carvings or writings upon the mezuzah (a vessel which houses a scroll of parchment with Biblical text written on it) that is situated upon all the door frames in a home or establishment.

Still another view is that "El Shaddai" is composed of the Hebrew relative pronoun She (Shin plus vowel segol), or, as in this case, as Sha (Shin plus vowel patach followed by a dagesh, cf. A Beginner's Handbook to Biblical Hebrew, John Marks and Virgil Roger, Nashville:Abingdon, 1978 "Relative Pronoun, p.60, par.45) The noun containing the dagesh is the Hebrew word Dai meaning "enough,sufficient, sufficiency" (cf. Ben Yehudah's Pocket English-Hebrew/Hebrew-English,New York, NY:Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster Inc.,1964,p. 44). This is the same word used in the Passover Haggadah, Dayeinu, "It would have been sufficient." The song entitled Dayeinu celebrates the various miracles God performed while extricating the Hebrews from Egyptian servitude. It is understood as such by The Stone Edition of the Chumash (Torah) published by the Orthodox Jewish publisher Art Scroll, editors Rabbi Nosson Scherman/Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz, Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah Publications,Ltd. 2nd edition, 1994, cf. Exodus 6:3 commentary p. 319. The Talmud explains it this way, but says that "Shaddai" stands for "Mi she'Amar Dai L'olamo" - "He who said 'Enough' to His world." When God was creating the world, He stopped the process at a certain point, holding back creation from reaching its full completion, and thus the name embodies God's power to stop creation.

It is often paraphrased in English translations as "Almighty" although this is an interpretive element. The name then refers to the pre-Mosaic patriarchal understanding of deity as "God who is sufficient." God is sufficient, that is, to supply all of one's needs, and therefore by derivation "almighty". It may also be understood as an allusion to the singularity of deity "El" as opposed to "Elohim" plural being sufficient or enough for the early patriarchs of Judaism. To this was latter added the Mosaic conception of YHWH as God who is sufficient in Himself,thatis,a self-determined eternal Being qua Being,for whom limited descriptive names cannot apply. This may have been the probable intent of "eyeh asher eyeh" which is by extension applied to YHWH (a likely anagram for the three states of Being past, present and future conjoined with the conjunctive letter vav), cf. Exodus 3:13-15.

Shalom

Shalom ("Peace"; Hebrew: שלום)

The Talmud says "the name of God is 'Peace'" (Pereq ha-Shalom, Shab. 10b), (Judges 6:24); consequently, one is not permitted to greet another with the word shalom in unholy places such as a bathroom (Talmud, Shabbat, 10b). The name Shlomo, "His peace" (from shalom, Solomon, שלומו), refers to the God of Peace. Shalom can also mean "hello" and "goodbye."

Shekhinah

Shekhinah (Hebrew: שכינה) is the presence or manifestation of God which has descended to "dwell" among humanity. The term never appears in the Hebrew Bible; later rabbis used the word when speaking of God dwelling either in the Tabernacle or amongst the people of Israel. The root of the word means "dwelling". Of the principal names of God, it is the only one that is of the feminine gender in Hebrew grammar. Some believe that this was the name of a female counterpart of God, but this is unlikely as the name is always mentioned in conjunction an article (e.g.: "the Shekhina descended and dwelt among them" or "He removed Himself and His Shekhina from their midst"). This kind of usage does not occur in Semitic languages in conjunction with proper names.

The Arabic form of the word "Sakina سكينة" is also mentioned in the Quran.This mention is in the middle of the narrative of the choice of Saul to be king and is mentioned as descending with the ark of the covenant here the word is used to mean "security" and is derived from the root sa-ka-na which means dwell:

- And (further) their Prophet said to them: "A Sign of his authority is that there shall come to you the Ark of the Covenant, with (an assurance) therein of security from your Lord, and the relics left by the family of Moses and the family of Aaron, carried by angels. In this is a Symbol for you if ye indeed have faith."

Yah

The name Yah is composed of the first two letters of YHWH. It appears often in names, such as Elijah or Joshua (Yehoshua). The Rastafarian Jah is derived from this, as is the expression Hallelujah. Found in the bible, Psalms 68:4. Different versions report different names such as: YAH, YHWH, LORD ,GOD and JAH.

YHWH Tzevaot

The name YHWH and the title Elohim frequently occur with the word tzevaot or sabaoth ("hosts" or "armies", Hebrew: צבאות) as YHWH Elohe Tzevaot ("YHWH God of Hosts"), Elohe Tzevaot ("God of Hosts"), Adonai YHWH Tzevaot ("Lord YHWH of Hosts") and, most frequently, YHWH Tzevaot ("YHWH of Hosts").

This compound name occurs chiefly in the prophetic literature and does not appear at all in the Torah, Joshua or Judges. The original meaning of tzevaot may be found in 1 Samuel 17:45, where it is interpreted as denoting "the God of the armies of Israel". The word, in this special use is used to designate the heavenly host, while otherwise it always means armies or hosts of men, as, for example, in Exodus 6:26, 7:4, 12:41.

The Latin spelling Sabaoth combined with the golden vines over the door on the Herodian Temple (built by the Idumean Herod the Great) led to false-identification by Romans with the god Sabazius.

HaMakom

"The Place" (Hebrew: המקום)

Used in the traditional expression of condolence; המקום ינחם אתכם בתוך שאר אבלי ציון וירושלים HaMakom yenachem etchem betoch shs’ar aveilei Tziyon V’Yerushalayim — "The Place will comfort you (pl.) among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem."

Seven Names of God

In medieval times, God was sometimes called The Seven.[25] Among the ancient Hebrews, the seven names for the Deity over which the scribes had to exercise particular care were:[26]

- Eloah

- Elohim

- Adonai

- Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh

- YHWH (i.e. the pronunciation Yahweh is not considered a legitimate name of God by most Jewish scholars)

- Shaddai

- Tzevaoth

Lesser used names of God

- Adir — "Strong One"

- Adon Olam — "Master of the World"

- Aibishter — "The Most High" (Yiddish)

- Aleim — sometimes seen as an alternative transliteration of Elohim

- Avinu Malkeinu — "Our Father, our King"

- Boreh — "the Creator"

- Ehiyeh sh'Ehiyeh — "I Am That I Am": a modern Hebrew version of "Ehyeh asher Ehyeh"

- Elohei Avraham, Elohei Yitzchak ve Elohei Ya`aqov — "God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob"

- Elohei Sara, Elohei Rivka, Elohei Leah ve Elohei Rakhel — "God of Sarah, God of Rebecca, God of Leah, God of Rachel"

- El ha-Gibbor — "God the hero" or "God the strong one" or "God the warrior"

- Emet — "Truth"

- E'in Sof — "endless, infinite", Kabbalistic name of God

- HaKadosh, Baruch Hu — "The Holy One, Blessed be He"

- Kadosh Israel — "Holy One of Israel"

- Melech HaMelachim — "The King of kings" or Melech Malchei HaMelachim "The King, King of kings", to express superiority to the earthly rulers title. Phillip Birnbaum renders it "The King Who rules over kings"

- Makom or HaMakom — literally "the place", perhaps meaning "The Omnipresent"; see Tzimtzum

- Magen Avraham — "Shield of Abraham"

- Ribbono shel `Olam — "Master of the World"

- Ro'eh Yisra'el — "Shepherd of Israel"

- YHWH-Yireh (Jehovah-jireh) — "The LORD will provide" (Genesis 22:13-14)

- YHWH-Rapha — "The LORD that healeth" (Exodus 15:26)

- YHWH-Niss"i (Yahweh-Nissi) — "The LORD our Banner" (Exodus 17:8-15)

- YHWH-Shalom — "The LORD our Peace" (Judges 6:24)

- YHWH-Ro'i — "The LORD my Shepherd" (Psalm 23:1)

- YHWH-Tsidkenu — "The LORD our Righteousness" (Jeremiah 23:6)

- YHWH-Shammah (Jehovah-shammah) — "The LORD is present" (Ezekiel 48:35)

- Tzur Israel — "Rock of Israel"

In English

The words "God" and "Lord" (used for the Hebrew Adonai) are often written by many Jews as "G-d" and "L-rd" as a way of avoiding writing a name of God, so as to avoid the risk of sinning by erasing or defacing his name. In Deuteronomy 12:3-4, the Torah exhorts one to destroy idolatry, adding, "you shall not do such to the Lord your God." From this verse it is understood that one should not erase the name of God. The general rabbinic opinion is that this only applies to the sacred Hebrew names of God — but not to the word "God" in English or any other language. Even among Jews who consider it unnecessary, many nonetheless write the name "God" in this way out of respect, and to avoid erasing God's name even in a non-forbidden way.

British folklore

A partial coincidence with this list appears in a medieval verbal charm from British folk medicine:

Kabbalistic use

The system of cosmology of the Kabbalah explains the significance of the names.

One of the most important names is that of the En Sof אין סוף ("Infinite" or "Endless"), who is above the Sefirot.

The forty-two-lettered name contains the combined names אהיה יהוה אדוני הויה, that when spelled in letters it contains 42 letters. The equivalent in value of YHWH (spelled הא יוד הא וו = 45) is the forty-five-lettered name.

The seventy-two-lettered name is based from three verses in Exodus (14:19-21) beginning with "Vayyissa," "Vayyabo," "Vayyet," respectively. Each of the verses contains 72 letters, and when combined they form 72 names, known collectively as the Shemhamphorasch.

The kabbalistic book Sefer Yetzirah explains that the creation of the world was achieved by the manipulation of the sacred letters that form the names of God.

Laws of writing divine names

According to Jewish tradition, the sacredness of the divine names must be recognized by the professional scribe who writes the Scriptures, or the chapters for the tefillin and the mezuzah. Before transcribing any of the divine names he prepares mentally to sanctify them. Once he begins a name he does not stop until it is finished, and he must not be interrupted while writing it, even to greet a king. If an error is made in writing it, it may not be erased, but a line must be drawn round it to show that it is canceled, and the whole page must be put in a genizah (burial place for scripture) and a new page begun.

The tradition of seven divine names

According to Jewish tradition, the number of divine names that require the scribe's special care is seven: El, Elohim, Adonai, YHWH, Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh, Shaddai, and Tzevaot.

However, Rabbi Jose considered Tzevaot a common name (Soferim 4:1; Yer. R. H. 1:1; Ab. R. N. 34). Rabbi Ishmael held that even Elohim is common (Sanh. 66a). All other names, such as "Merciful," "Gracious," and "Faithful," merely represent attributes that are common also to human beings (Sheb. 35a).

See also

- Names of God in Christianity

- Baal Shem

- Besiyata Dishmaya

- Jehovah

- Names given to the divine

- Names of God

- Ten Commandments

Notes

- ↑ eg Siddur Lev Chadash (1995), the standard prayerbook used by Liberal Judaism in the UK

- ↑ Tetragrammaton ) - Information from Reference.com

- ↑ http://www.karaite-korner.org/yhwh_2.pdf

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L.. Understanding the Bible: a reader's introduction, 2nd ed. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. page 21.

- ↑ Until at least 1999 this site used the reverent YDWD substitution in Hebrew letters, and then all instances were converted to "HaShem", including at Exodus 6.2, but the one at Exodus 6.3. The switch occurred at some point between these two archives of the Breslov.com version of the electronic JPS Bible:

– ""Exodus 6"". Archived from the original on 1999-10-08. http://web.archive.org/web/19991008190052/http://www.breslov.com/bible/Exodus6.htm#3. "[...] by My name ידוד [...]" (source document requires the "Web Hebrew AD" font)

– ""Exodus 6"". Archived from the original on 2001-02-16. http://web.archive.org/web/20010216163146/http://www.breslov.com/bible/Exodus6.htm#3. "[...] by My name Jehovah [...]"

The site maintainer states that he applied some adaptations to the electronic JPS in order to generate his own version, and that "The name of L-RD has been written as HaShem"[1], so this single instance of "Jehovah" looks like an odd case of automated conversion error. - ↑ "Stanley S. Seidner,"HaShem: Uses through the Ages." Unpublished paper, Rabbinical Society Seminar, Los Angeles, CA,1987.

- ↑ Seidner, 4.

- ↑ Seidner, 4.

- ↑ Seidner, 5.

- ↑ Exodus 3:14 LXX

- ↑ Yonge. Philo Life Of Moses Vol.1 :75

- ↑ Life of Moses I 75, Life of Moses II 67,99,132,161 in F.H. Colson Philo Works Vol. VI, Loeb Classics, Harvard 1941

- ↑ Rev.1:4,1:8.4:8 UBS Greek Text Ed.4

- ↑ New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc., International Bible Students Association, Brooklyn, New York, U.S.A., Exodus 3:14, Footnote

- ↑ K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, "Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible", pp.274-277

- ↑ K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, "Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible", pp.277-279

- ↑ Torrey 1945, 64; Metzger 1957, 96; Moore 1992, 704,

- ↑ Mark S. Smith, "God in translation: deities in cross-cultural discourse in the biblical world", p.15

- ↑ R. Toporoski, "What was the origin of the royal "we" and why is it no longer used?", (The Times, May 29, 2002. Ed. F1, p. 32)

- ↑ Gesenius' Hebrew Grammar (A. E. Cowley, ed., Oxford, 1976, p.398)

- ↑ The inscription offers only a fragmentary Sh... (Harriet Lutzky, "Ambivalence toward Balaam" Vetus Testamentum 49.3 [July 1999, pp. 421-425] pp 421f.

- ↑ Lutzky 1999:421.

- ↑ J.A. Hackett, "Some observations on the Balaam tradition at Deir 'Alla'" Biblical Archaeology 49 (1986), p. 220.

- ↑ Harriet Lutzky, "Shadday as a goddess epithet" Vetus Testamentum 48 (1998) pp 15-36.

- ↑ The Reader's Encyclopedia, Second Edition 1965, publisher Thomas Y. Crowell Co., New York, editions 1948, 1955. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 65-12510, page 918

- ↑ The Facts on File Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins (Robert Hendrickson, 1987) [2] ISBN 0816040885 ISBN 978-0816040889

- ↑ "seven". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2nd ed. 1989.

- ↑ Forbes, Thomas R. Verbal Charms in British Folk Medicine. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 115(4). Aug 1971. pp. 293-316. p 297.

References

- Driver, S.R., Recent Theories on the Origin and Nature of the Tetragrammaton, Studia Biblica vol. i, Oxford, (1885)

- Mansoor, Menahem, The Dead Sea Scrolls. Grand Rapids: Baker, (1983)

- W. F. Albright, The Names Shaddai and Abram". Journal of Biblical Literature, 54 (1935): 173–210

Further reading

- Harris Laird, Archer, Gleason Jr. and Waltke, Bruce K. (eds.) Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, 2 vol., Moody Press, Chicago, 1980.

- Hoffman, Joel M. In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language, NYU Press (2004). ISBN 0-8147-3690-4.

- Joffe, Laura, "The Elohistic Pslater: What, How and Why?", Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament, vol 15-1, pp. 142–169 Taylor & Francis AS, part of the Taylor & Francis Group., June 2001.

- Kearney, Richard, "The God Who May be: A Hermeneutics of Religion", Modern Theology, January 2002, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 75–85(11)

- Kretzmann, Paul E., Popular Commentary of the Bible, The Old Testament, Vol. 1. Concordia Publishing House, St. Louis, Mo. 1923.

- Shaller, John, The Hidden God, The Wauwatosa Theology, vol. 2, pp. 169–187, Northwestern Publishing House, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1997.

- Stern, David. Jewish New Testament Commentary, Jewish New Testament Publications, Inc., Clarkville, Maryland, 1996.

- Strong, James, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, New York and Nashville, 1890.

- Tov, E., "Copying a Biblical Scroll", Journal of Religious History, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 189–209(21), Blackwell Publishing, June 2001

- van der Toorn, Karel (1995). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. New York: E.J. Brill. ISBN 0-80282-491-9.

- Vriezen, Th. C., The Religion of Ancient Israel, The Westminster Press, Philadelphia, 1967.

External links

- A Christian Discussion of the pronunciation of YHWH, including a new theory that explains all theophoric elements

- God's names in Jewish thought and in the light of Kabbalah

- The Name of God as Revealed in Exodus 3:14 - an explanation of its meaning.

- Bibliography on Divine Names in the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Names of God

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||